There was no Ada Louise Huxtable to stand up for the Hotel Pennsylvania in braindead New York City. She saved the New York Public Library from ruin, but now she’s gone. Instead, the corrupt, Ford Foundation run New York Times architecture critic was silent — so much for fake interest in low-income housing and learning from the mistakes of the notorious Penn Station demolition.

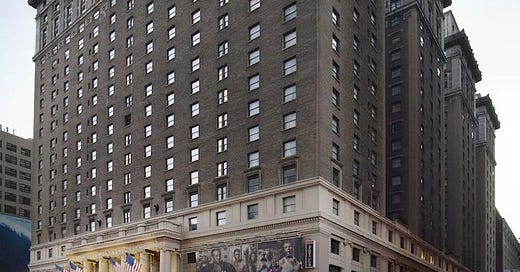

The limestone and brick Hotel Pennsylvania was designed in 1916 by McKim, Mead and White, opened in 1919, and operated for 101 years until its closing in 2020 by Vornado Realty Trust. It contained 2200 rooms (that could have been redesigned by a more thoughtful developer), ballrooms and hallways that were neglected over time. 60s or 70s-era renovations of its public spaces watered down the original grandeur and gave away public space to TV studios. The bad reputation was superficial — tacky rooms and lobby spaces lost original Italian-style grandeur and replaced it with the atmosphere of the current underground Penn Station, along with signs of neglect common in prewar New York buildings — reports of bedbugs, worn furniture, torn wallpaper.

The same bureaucratic villains are behind the scenes in most preservation or New York urban design stories — the compromised Landmarks Preservation Commision (McKim, Mead and White, hello!), the visionless Vornado real estate company, the corrupt New York Times (reliant on real estate ads and foundation money).

With false promises of a new 1200-foot supertall PENN15 designed by Foster & Partners now vanished, the two-block area is being developed by Vornado into “Penn Platform”, a series of tennis courts. Tennis courts! Have not yet seen the new Megalopolis movie (too weird to take the wife), but its themes of design vs bureaucracy ring true. New York City is in desperate need of a Design Authority to find alternative plans and perhaps inject some grace and vision into fake rational status quo of Foster-style blocky industrial buildings.

Learning from Pennsylvania Hotel

Now that the 22-floor, four-part building is demolished, let’s learn from it to find a better solution than another dumb glass office tower or worse, tennis courts.

Look at the classic proto-modern 3-part design — a grand, limestone base containing Italian-style ballrooms and grand public entrance marked by a colonnade. You don’t often see grand, unprogrammed public spaces in modern apartment buildings, much less office towers (you will get a small, dank lobby with a doorman). The base of Penn Hotel had been converted into shoddy 70s era entrance with television studios, cutting down the monumentality into pieces. Only a few dated conference rooms remained. A design rethink could have returned this space to real public or resident use. With vision.

Next, the brick tower spaces, divided by McKim, Mead and White into four parts and wrapping around courtyards. Many prewar New York buildings used courtyards to maximize light and air, though it probably isn’t ideal to have a bedroom view looking across to a brick wall. But light and air is better than nothing. There is enough court space to give breathing room. The weakness is in the dark double-loaded apartment corridors, which I recall in a similar era building, the Herald Square Towers on 34th street. These are depressing and need to be opened up to light and air. This could be remedied on redesign by converting a few apartments into hallway public spaces.

On top is the crown, the penthouse spaces. These would likely be the easiest to convert and modernize. There are myriad uses, commercial or private, that could be had from four large spaces like this.

Design culture and authority

New York is lucky to have so much embedded design infrastructure, built during the golden age of early industrialization until about the 1970s. Since then, design vision has disappeared into smaller scale redevelopment projects such as the High Line and oversized office towers like at 270 Park and Hudson Yards. The latter has been an unfortunate model for haphazard bureaucratic design. As it was supposed to fill in much of the high-end residential and office space needs, many of its buildings are still empty and the area mostly dead and devoid of life. Penn Hotel, on the other hand, is filled with energy and life feeding from the railroad station, subways, Madison Square Garden and midtown energy.

Hotel Pennsylvania and Vornado could have easily completed a traditional or contemporary redesign, looking at successes like the Pittsburgh Hotel Penn that now looks similar to New York Hotel Penn in its glory days. Or they could have hired a forward-thinking architect like TenBerke that transformed an abandoned but grand HH Richardson Buffalo asylum into a luxury retreat.

Either way, the lack of alternatives and the conveniently defeatist attitude of New York bureaucrats and their media pawns is a betrayal of both design culture, New York City and the social issues these critics pretend to care about — affordable housing, accessibility, social justice. Hotel Pennsylvania did not die on its own, it was murdered in order to make way for tennis courts. Perhaps it’s time for a New York Design Authority with real power to push back against fake Landmarks Preservation and New York Times critics. Then we can find better solutions for Penn Hotel, Sunnyside Yards and more.